06.03.25

GMA Insights | Why System Boundaries Matter: Exploring Various Market-based Approaches to Deep Value Chain Decarbonization

INTRODUCTION

Welcome back to GMA Insights, a series where we explore concepts related to high-integrity market-based value chain decarbonization. In the first installment of the series, we introduced the concept of chain of custody models and explained “book and claim” – the model used most often by GMA – in greater detail.

But why do different chain of custody models exist? Is one “better” than another? In short, which model is “best” will depend on the situation, and on the goals of the company applying the model. Each model follows a unique methodology and has its own set of rules. Some are focused on detailed tracking of physical products within a system. Others focus more on tracking the characteristics inherent in a set of products or materials, whether or not these characteristics keep their 1:1 attachment to physical products within that system.

Today, we’ll do a deeper dive into two different chain of custody models: book and claim and mass balance. We’ll explain how each of them works and the rules that must be followed within each model. Given that companies can – and do – use both of these models to track the impact of their decarbonization efforts, we’ll explore why one might be preferable to another, depending on which goals an organization is trying to achieve.

So let’s get to it, starting with some fundamentals about both the book and claim and mass balance models.

MASS BALANCE CHAIN OF CUSTODY MODEL

A mass balance chain of custody model allows for physical mixing of materials with specified characteristics with other materials that do not have those characteristics. Despite this physical mixing, in a mass balance model the materials with specified characteristics are tracked as they move through a process or distribution system. The total amount of materials that are documented entering the process or system must match (taking into account process or system losses) the amount of materials that are documented coming out of the process or system.

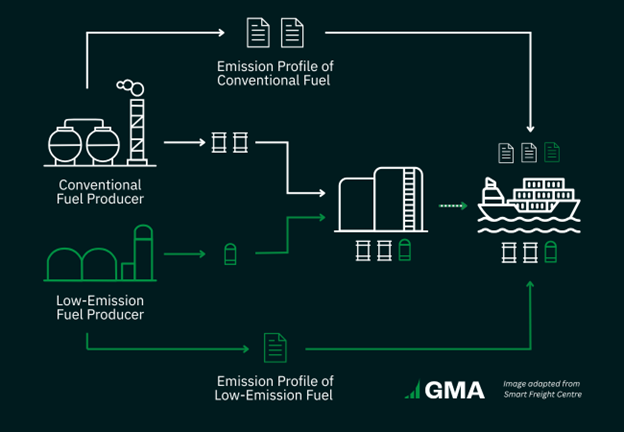

For example, in a fuel distribution network a low emission fuel may be mixed with a fossil fuel that does not have a low emission profile. If a mass balance model is employed, at each phase in the fuel distribution network, the amount of low emission fuel and the amount of fossil fuel is tracked and documented. That is, the distribution network managers would know that, of X gallons of fuel in a storage facility in the network, Y gallons are theoretically low emission fuel and Z gallons are theoretically fossil fuel. The number of low emission fuel attributes assigned to fuel withdrawn from the fuel distribution network must match the number of gallons of low emission fuel that was added to the network. See Figure 1.

Figure 1: A mass balance chain of custody model.

BOOK AND CLAIM CHAIN OF CUSTODY MODEL

A book and claim chain of custody model also allows for physical mixing of materials with specified characteristics with other materials that do not contain those characteristics. In a book and claim model, though, the amount of materials with specified characteristics does not need to be tracked and documented at each step of the process or distribution system. Instead, the characteristics of the inputs are completely decoupled from the physical materials at or before the point of mixing. These characteristics are then tracked separately from the flow of the physical material. The materials’ characteristics are recorded and transferred in a documentation system (e.g., a registry) to ensure the integrity of accounting for these characteristics.

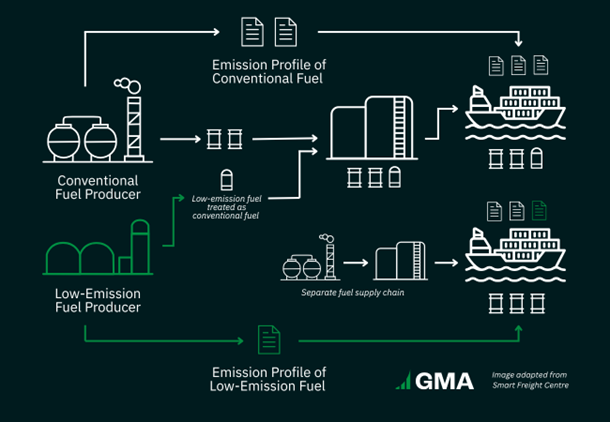

Applying these ideas to our example from above, a low emission fuel may still be mixed with a fossil fuel that does not have a low emission profile. But under the book and claim model, the low emission fuel’s emission attributes are completely separated from the fuel before or at the point of mixing. Once the low emission fuel and fossil fuels are mixed, the combined physical fuel is treated as if it had no low emission characteristics. The attributes of the low emission fuel are tracked and transacted independent of the physical fuel product. See Figure 2.

Figure 2: A book and claim chain of custody model.

Program spotlight: The Sustainable Aviation Buyers’ Alliance (SABA), a program that GMA runs in partnership with Environmental Defense Fund and RMI, relies on the book and claim model. Sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) is mixed with conventional jet fuel, with the physical mix of SAF and conventional jet fuel distributed and sold as though it were all conventional jet fuel. The low emission attributes of the SAF are completely separated from the physical SAF and transacted by means of SAF certificates in the SAFc registry.

THE IMPORTANCE OF SYSTEM BOUNDARIES

A chain of custody model’s boundary, in general terms, establishes where a company draws the line to ensure that products and characteristics going into a system (e.g. a manufacturing or refining process) match those emerging at the end. It may be surprising to see how much this decision can impact how companies can assign characteristics to their products.

Let’s explore this idea by imagining a bustling metropolis that’s home to many companies that specialize in baking wheat into delicious loaves of bread.

Company 1: Mass Balance with a Bakery Level System Boundary

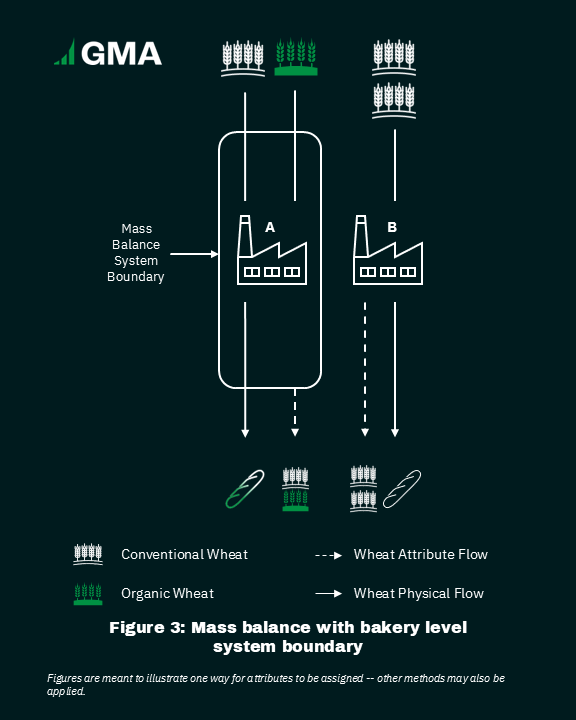

Company 1 operates two bakeries: Bakery A and Bakery B.

Bakery A receives both conventional wheat and organic wheat from its wheat suppliers. The conventional wheat and organic wheat are mixed together at the bakery and made into bread.

Bakery B does not use any organic wheat to make bread.

The company applies a mass balance chain of custody model to attribute wheat characteristics to loaves of bread, and sets the model boundary at the bakery level. See Figure 3 below.

While Company 1 cannot be sure that every single loaf of bread baked at Bakery A contains organic wheat, the company does know that over a certain period of time, the wheat in the loaves of bread (in totality) baked at Bakery A was 50% organic wheat.

In this example, the system boundary (i.e., Bakery A) matches the boundary for material (i.e., wheat) flows. A buyer sourcing all of the bread from Bakery A would receive, over the period of time during which Bakery A conducted its mass balance[1], bread that physically contained 50% organic wheat.

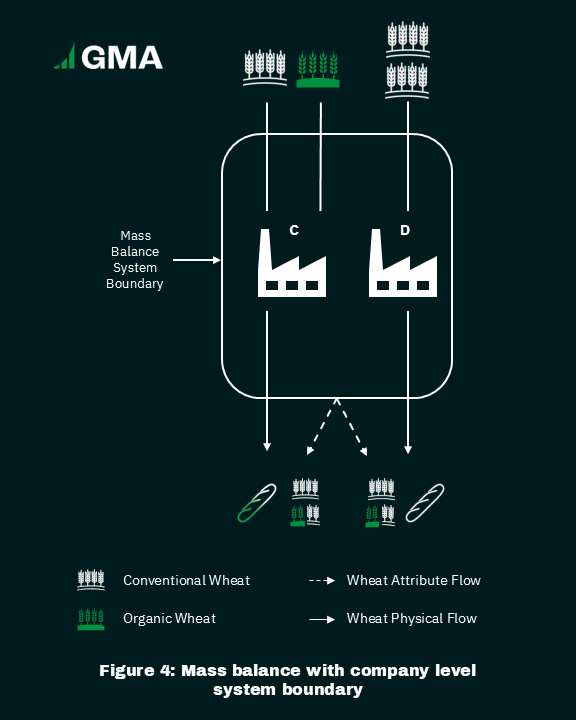

Company 2: Mass Balance with a Company Level System Boundary

Company 2 also operates two bakeries: Bakery C and Bakery D. The inputs for the two bakeries are the same as they were in the previous example, but the system boundary is drawn in a different place.

Bakery C receives 50% conventional wheat and 50% organic wheat from its wheat suppliers. The conventional wheat and organic wheat are mixed together at the bakery and made into bread.

Bakery D does not use any organic wheat to make bread.

The company applies a mass balance chain of custody model to attributing wheat characteristics to loaves of bread, and sets the model boundary at the company level. See Figure 4 as follows.

Unlike Company 1, Company 2 has set its mass balance system boundary at the company level. As such, Company 2 may attribute the characteristic of “organic wheat” to bread that has no chance of physically containing organic wheat (i.e., bread from Bakery D).

In this example, the system boundary (i.e., the company) does not match the boundary for material (i.e., wheat) flows. The amount of organic wheat attributed to the bread that buyers are purchasing is no longer linked to the amount of organic wheat that is physically in the bread that they receive.

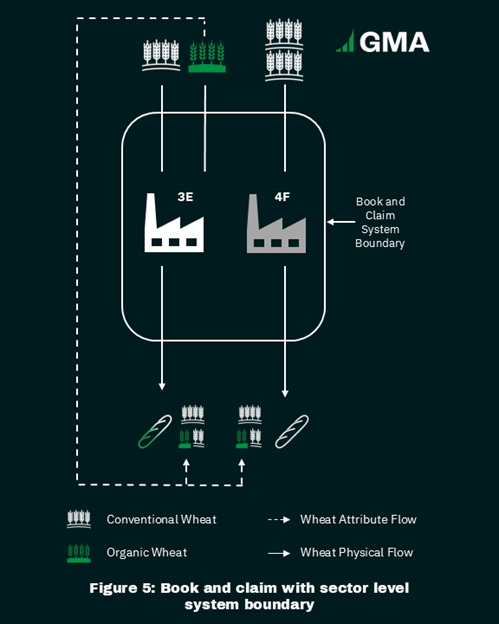

Companies 3 and 4: Book and Claim with a Sector Level System Boundary

Our next two companies each operate one bakery: Company 3 operates Bakery E, and Company 4 operates Bakery F. For the purposes of this example, together these two companies make up the bread sector.

Bakery E receives both conventional wheat and organic wheat from its wheat suppliers. The conventional wheat and organic wheat are mixed together at the bakery and made into bread.

Bakery F does not use any organic wheat. See Figure 5, below.

Company 3 applies a book and claim chain of custody model to attributing wheat characteristics to loaves of bread. Although some organic wheat is in the bread from Bakery E, Company 3 does not trace this wheat. Instead, Company 3 separates the organic attributes from the organic wheat before that organic wheat is mixed with conventional wheat at Bakery E. Company 3 then sells the attributes of that organic wheat to both companies buying bread from its own bakery – Bakery E – as well as to companies buying bread from a different company – Company 4 – which makes bread at Bakery F.

Now, take a look back at Figure 4 and compare it to Figure 5. Even though Company 2 applied a mass balance model and Company 3 applied a book and claim model, in both cases organic wheat characteristics are attributed to loaves of bread that have no chance of physically containing any organic wheat.

CONCLUSION

So is one chain of custody model “better” than another? Does one do a more accurate job of tracking and measuring special characteristics of physical products and giving customers a way to buy materials that “have” those characteristics? Is one model better than another at helping companies achieve their decarbonization goals?

Well, it depends. As we saw in the bakery examples above, the system boundary can have just as big an influence as the chain of custody model on the link – or lack of a link – between the characteristics and the physical composition of a batch of products.

What does this mean for decarbonizing heavy industry? Well, if you buy steel that has been attributed low emission characteristics through a mass balance model, that doesn’t necessarily mean that you will physically receive any low emission steel. The physical steel you receive might be low emission steel… but it also might not be. It depends.

Because the mass balance model maintains a closer tie between physical products and their special characteristics, some people think that the mass balance model is inherently more accurate than book and claim. As we see it, the value of an approach lies in its ability to achieve objectives. If a company’s objective is to support the decarbonization of its physical steel suppliers (meaning, at minimum, it knows who they are and that they are likely to remain the same), then a mass balance approach with a company-wide system boundary will work fine.

If a company has any other objective – for example, if its supply chain isn’t as straightforward as the examples above, then the book and claim model becomes indispensable.

Some may also think that mass balance approaches are inherently more credible than book and claim. The issue of credibility in chain of custody systems will be explored in a future edition of GMA Insights.

[1] Provided that there is not crediting of attributes across mass balancing periods (i.e., the amount of time during which the mass balance is calculated). If Company 1 credited organic wheat attributes across mass balancing periods, there is the possibility that no loaves of bread from one period would contain organic wheat, and that those loaves of bread could be attributed the characteristics of organic wheat from a previous period. For more details on crediting across balancing period, see ISO Standard 22095.